Posted on - 17 Mar 2022

For much of last week, I wondered if writing the rest of this article might be effectively moot. But life goes on, and trading goes on too. Even if nickel trading on the London Metal Exchange doesn’t currently go on (as I write this it’s suspended – again – after it nominally restarted on Tuesday). And, indeed, the question of how much nickel trading will go on in the future on the LME is quite an apt one.

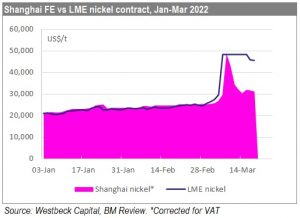

Anyway, annoyance of traders with the LME apart, we can remember that the LME is not the only metal exchange out there. For the past 2-3 days, I’ve been using the Shanghai Futures Exchange nickel contract to understand what’s been going on in the nickel market.

Anyway, annoyance of traders with the LME apart, we can remember that the LME is not the only metal exchange out there. For the past 2-3 days, I’ve been using the Shanghai Futures Exchange nickel contract to understand what’s been going on in the nickel market.

Over the past 14 months (if one backs out the past 14 days), there’s been a 96% correlation between Shanghai FE nickel and LME cash nickel, so the Shanghai contract provides a pretty reasonable price indication for nickel metal.

And the Shanghai FE data suggests that now the short squeeze is over, nickel metal is currently trading at c.US$31,000/t. While that’s up on where it was before the short squeeze, it still leaves quite a lot of additional upside over the course of this year, in my view. [And by the way, with an 8% day limit on the LME it’s going to take a while before LME prices reach the likely “true market” level].

So, back to the focus of this blog series, and why I prefer nickel over copper. In the last blog I discussed why I believe the story on copper is overhyped. In this blog I’m going to talk about why I believe the story on nickel is being under-appreciated by the market.

Most of this comes down to the fact that I believe that the market is wrong on its nickel supply forecasts in the near-term, although nickel demand growth forecasts are starting to be more realistic.

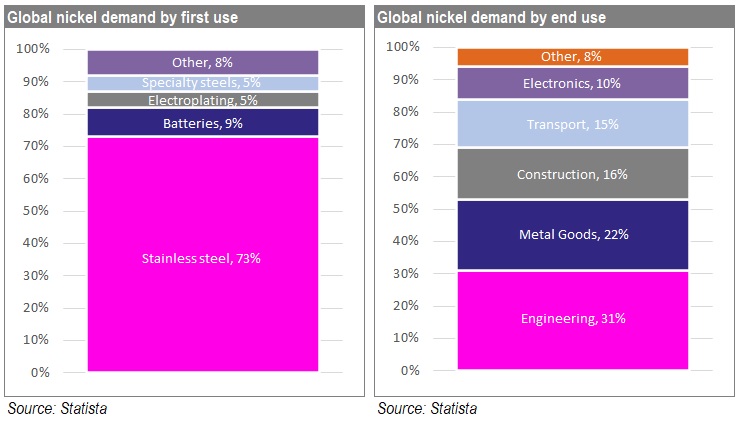

Let’s first talk about the demand structure for nickel as it compares to copper. I think there’s a temptation among generalists to assume that all base metals have very similar demand drivers, but that simply isn’t the case.

In the last article I talked about the importance of the construction markets to copper demand. Globally, 30-40% of all copper is used in the construction industry, primarily as wires or pipes. But nickel simply doesn’t have that sort of exposure to the construction industry. In fact, on latest data, only 16% of nickel’s end use exposure is in the construction industry, mostly as decorative elements on facades.

It’s very important to understand the structure of nickel demand, primarily at its first use level, to understand its end use structure.

Indeed, 73% of nickel used in the world goes into stainless steel as its first use. This usage then has significant implications into nickel’s end usage pattern.

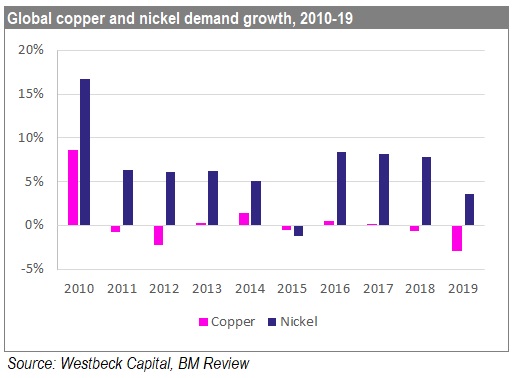

This makes nickel’s end use demand profile totally different from copper’s, which means that its demand growth profile has also been totally different in recent years and is likely to remain different going forward.

Indeed, while global copper demand struggled to exceed 1% average annual growth rate between 2010-19, nickel demand toddled along very nicely, thank you, at 6.7% pa. And now, if you add the battery industry into the equation, there’s a major secular demand growth driver on top of that.

While, if I was writing this piece a year ago, I would be suggesting that most sellside analysts were understating nickel demand from the EV industry, now on balance I don’t believe that to be the case any more. Most analysts have started to raise their nickel demand forecasts from EVs and that’s all well and good.

What that means though, is that incorporating other uses, nickel demand is set to continue to rise at 6-8% per annum on average for the next several years. If high nickel batteries manage a higher market share than I currently forecast (to the level that many analysts currently forecast), that level could be somewhat higher.

So, I’m not massively more bullish than the sellside on demand (although still a little bit) but where I do disagree substantially with the sellside is on nickel supply.

The reason that the market has been so ambivalent about the outlook for nickel prices in recent years has been because of the investments in Indonesian HPAL capacity by a number of Chinese companies and their partners over the past several years.

Three major HPAL projects were set to start up in 2021-22 which, most analysts suggested, together would reach 115Ktpa of nickel production by 2023E.

But the problem is that they haven’t. And, in my view, they won’t.

And the reason is simple – waste.

Waste from HPAL plants is highly acidic. And there’s lots of it. Think about that for a second. Most laterite orebodies have c.1% nickel grades. So, if you want to produce 40Ktpa of nickel then you need to mine c.4Mtpa of material which goes through your plant and comes out with a pretty low (ie very acidic) pH. Some projects get around that by backfilling it and some simply stick it into the sea.

The Indonesian HPAL projects had planned to dispose of their tailings offshore. But Indonesia has recently outlawed offshore dumping of waste. Which means that these projects need to backfill it and they need to quite substantially re-engineer their tailings disposal plans to be able to safely dispose of large amounts of acidic waste material. And they can’t reach anything like intended production levels until they sort out how they’re going to dispose of their waste material.

Which means that Indonesia won’t be producing 120Ktpa of HPAL-derived nickel by 2023, as most sellside models are suggesting, and they certainly won’t be producing c.60Kt in 2022. In fact, I’d be surprised if they did more than half of that.

Which means that most analysts are considerably overstating (class 1) nickel supply.

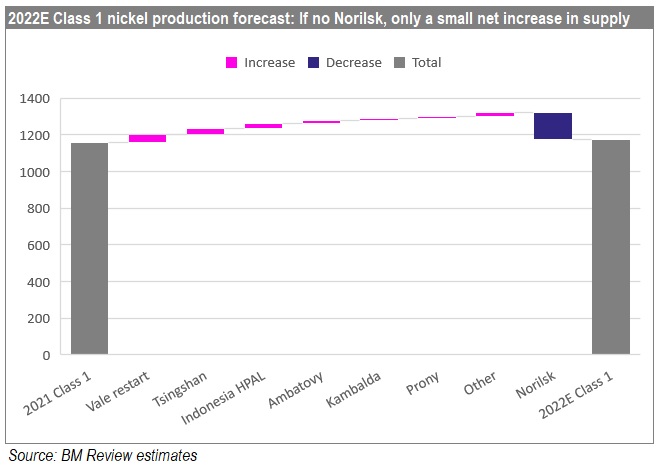

Now, let’s be realistic, class 1 nickel supply was impaired in 2021. We had the Sudbury strike and the Norilsk water incursion, among sundry operating issues at other mines. I estimate that class 1 nickel production in 2021 was perhaps 100Kt lower than it would ordinarily be. So, we should see more material available in the market this year than we did last year. But will we see enough to offset strong demand from the battery industry? I don’t believe so.

And, of course, this doesn’t include how much supply we could potentially lose from Russia. Norilsk Nickel was 14% of class 1 nickel production in 2019 (the last non-Covid-affected year). If Norilsk’s material is not available for the market, that’s going to tighten it out even further than analysts over-estimating Indonesian supply…

Much has been made of the announcement by Chinese steel producer Tsingshan that it has a method for producing battery grade nickel sulphate from nickel matte derived from nickel pig iron.

As I’ve noted in previous blogs, I think there are two issues with this which will impact its commercialisation: 1) It’s a very power-intensive methodology, which is likely to be a drawback in a world with high coal and hydrocarbon costs; and 2) because it is a very carbon-intensive method, it’s unlikely to be acceptable as a source of nickel for most Western World OEMs. We therefore only expect this process to be acceptable to Chinese OEMs and most Chinese OEMs are focused on LFP for mass market vehicles. We therefore don’t see potential for substantial battery grade nickel production from nickel matte.

As I’ve discussed in Battery Materials Review and on our Recharge podcast, there are some interesting technologies for nickel production on the horizon. Perhaps the most potentially impactive on a large scale is the DNi method for processing laterite ores.

However, this is some way out (1-2 years) from being proven on a commercial scale, and hence more years from making a substantial impact in terms of industry volumes.

We are hopeful that some of these more environmentally-friendly processing methodologies can prevail, but we don’t see them making a substantial impact in terms of supply for at least 3-4 years.

This means that the supply/demand balance for nickel (particularly class 1 nickel) will likely be even tighter than sellside consensus is forecasting over the next 1-2 years.

This means that the supply/demand balance for nickel (particularly class 1 nickel) will likely be even tighter than sellside consensus is forecasting over the next 1-2 years.

Demand growth rates of 6-8% are likely over the next five years. Supply of battery grade nickel was unlikely to match that even before the Ukraine crisis. With Russian production now likely to be embargoed for an extended period, I see the market being very tight indeed in the near-term. That should help nickel prices to re-rate from current levels.

I will discuss that a bit more in the last section of this blog.

Matt Fernley is Editor of Battery Materials Review and Head of Research for Westbeck Capital’s Volta Energy Transition fund.